The four main nominalisers

이

먹이

food

(으)ㅁ

걸음

a step

기

여행하기

(act of) travelling

M 것

공부하는 것

(act of) studying

Contents

Introduction

Nominalisation is where something (normally a verb) becomes a noun, basically. Consider the following examples of nominalisation using the four main nominalisers (이, ㅁ, 기, M 것).

이

먹다 → 먹이 = 먹+이

to eat → food

(으)ㅁ

걷다 → 걸음 = 걸+음

to walk → a step

기

여행하다 → 여행하기 = 여행하+기

to travel → (act of) travelling

M 것

공부하다 → 공부하는 것 = 공부하+는+ 것

to study → (act of) studying

With the above examples, we see how the verb takes a ‘nominaliser‘ (이, ㅁ, 기 or M 것) and becomes a noun.

There are two big questions regarding Korean nominalisers:

• Why do the three primary nominalisers ㅁ, 기 and 것 appear to perform the same function? Why do they overlap?

• When are ㅁ, 기 and 것 used and how are they different? Are they interchangeable?

The number of nominalisers in Korean is debatable because there are multiple ways of looking at grammar. We will say there are three primary nominalisers in Modern Korean: ㅁ, 기 and 것. Some scholars consider 이 and/or 지 to also be part of this list. The nominalisers each have different meanings and are used for different reasons. 것 is undoubtedly the most productive (able to do the most) nominaliser in Korean. 기 is to some accounts the most frequent but has lost ground to 것. ㅁ much is less frequent and less productive than both 것 and 기. 이 isn’t a fully-fledged a nominaliser because its use is restricted to fossilised forms (explain later). 지 is interesting because it’s sometimes classified as a nominaliser, sometimes as a verb ending.

Why is nominalisation used?

Why do languages use nominalised forms rather than simply using verbs? What exactly happens in the nominalisation process?

Say you want to talk about a concrete entity, such as a book or a chair. These items are easy to conceptualise as they have distinct conceptual borders. If someone randomly says the word ‘book’, you can easily picture a book in your mind because the item is easily conceptualised.

Now imagine you want to talk about an abstract thought or process, such as ‘the act of travelling’. Such entities are difficult to conceptualise because they do not have distinct conceptual borders. Nominalisation is a process of taking something conceptually complicated and making it simple. It takes an abstract thought and makes it a concrete entity.

여행하기

(act of) travelling

To explain it another way, imagine you want to describe some ‘thing’ which you cannot make sense of. Since the idea is difficult to conceptualise, it is difficult to communicate. In English, you might use phrases such as “the thing that…” or “the thingy which is…”. This is essentially what happens in nominalisation. It gives a concrete name to something and makes it easier to conceptualise by reducing a complex action/state into a noun. Nouns make things easier to talk about.

The most productive nominaliser in Korean is 것, which basically means ‘thing’. It is used to describe something abstract by saying “X is a thing”.

높은 것

(The thing of) being high

공부하는 것

(The thing of) studying

혼자 있는 것

(The thing of) being alone

되지 말아야 할 것

The thing that should not be

In fact, 것 is suggested to have originated from a word similar to 같 (Modern Korean), which means ‘skin’, ‘fur’, ‘surface’ or ‘appearance’. One can imagine how describing outward appearances became used to describe abstractions. This is how 것 became a nominaliser.

History of Korean nominalisers

The history of Korean nominalisers helps explain when the different nominalisers are used in contemporary Korean.

In Old Korean (until the 14th century), there were six nominalisers:

ㄹ, ㄴ, ㅁ, 이, 기, 디.

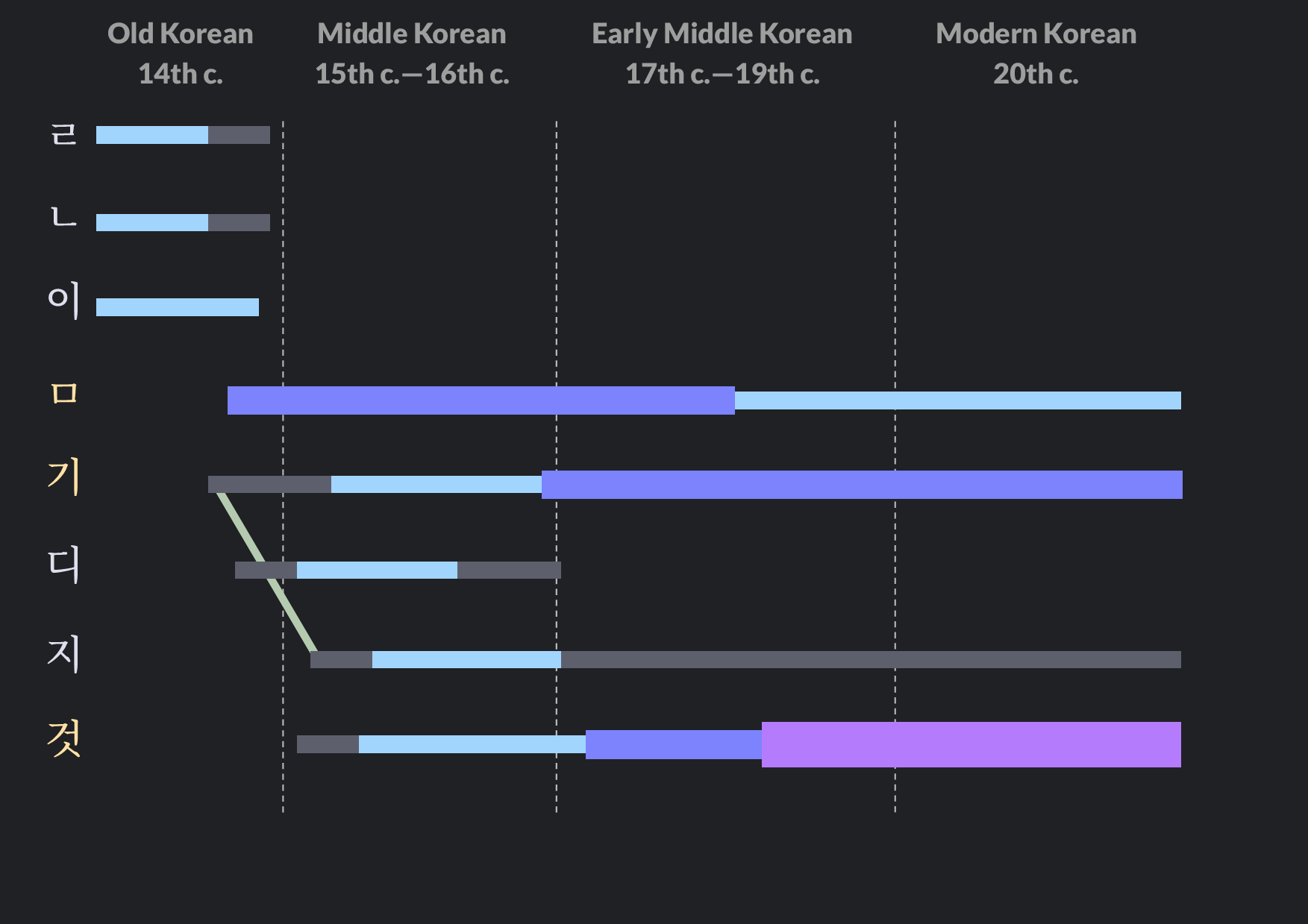

The diagram below (simplified from Rhee 2008) shows the development of nominalisers over time. This is important to consider because it illustrates how the primary nominalisers (ㅁ, 기 and 것) can be used with overlap.

Of interest are the primary nominalisers in Modern Korean (ㅁ, 기 and 것) which compete with each other. We see that ㅁ had prominence until overtaken by 기, and then 기 had prominence until overtaken by 것. ㅁ is currently the least productive of three, with somewhat limited use. 기 and 것 are the most commonly used with 것 being the most productive. See below for differences between ㅁ, 기 and 것.

The nominalisers ㄹ and ㄴ disappeared into becoming the adnominal modifiers ㄹ and ㄴ.

이 once had a varied function as a nominaliser, where it nominalised verbs, adjectives, nouns and onomatopoeic words. While it’s sometimes considered a nominaliser in Modern Korean, it really only appears in fossilised forms.

기, 디 and 지 are connected with a line because they originated from the same source lexeme meaning ‘place’. The nominaliser 디 was short-lived and is believed to have originated from 기. The two were in competition and with its disappearance, 디 became 지 (note the phonetic similarity), where it was downgraded to a limited role of nominalising negative sentences (while 기 was used elsewhere). From this comes the morpheme 지 which is used in several common grammatical constructions. 기 maintained its dominance until being gradually overtaken by 것 in Modern Korean.

The four main nominalisers

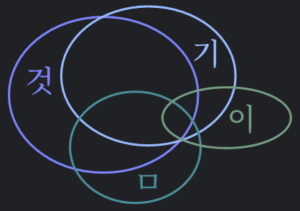

The four main nominalisers have a certain degree of exclusivity and a certain degree of overlap; as illustrated by the diagram below.

About 이

이 was once a nominaliser but is no longer considered so in normative grammar. Its use has weakened over time and typically only occurs with fossilised nouns. There is rarely any productive nominalisation taking place.

먹다 → 먹이 = 먹+이

to eat → food

덥다 → 더위 = 더워+이

to be hot → hot (weather)

Here 먹이 will be listed in the dictionary as its own word – a noun in its own right.

In Modern Korean, 이 has the function of naming entities based on onomatopoeic words or characteristic shapes. This includes a large number of fish, insects and birds; as well as entities named using child language.

부엉부엉 → 부엉이 = 부엉+이

onomatopoeia (hoot) → one that makes the sound 부엉부엉 (an owl)

빵빵 → 빵빵이 = 빵빵+이

onomatopoeia (horn) → one that makes the sound 빵빵 (a car)

뚱뚱 → 뚱뚱이 = 뚱뚱+이

shape: roundish → one that looks 뚱뚱 (a fat person)

A list of such 이 resultant nouns can be found here.

About ㅁ

Nominaliser ㅁ is less productive than both 기 and 것. It is often used in formal or written styles and is often substituted by 것 in casual speech. ㅁ tends to be used with completed actions and abstract thoughts and ideas.

기쁘다 → 기쁨 = 기쁘+ㅁ

to be happy → happiness

믿다 → 믿음 = 믿+음

to believe → belief

A list of such ㅁ resultant nouns can be found here.

ㅁ is suggested to have originated from a verb meaning ‘regard/consider’. This is interesting because nowadays when compared with 기 or 것, ㅁ tends to be favoured when denoting entities of knowledge and belief. ㅁ is usually the nominaliser of choice when writing abbreviated sentences for public signs, tech notifications and notes.

신호 없음.

No signal.

인터넷 연결 없음.

No internet connection.

알바 구함.

Part-time worker wanted.

나이제한 없음.

No age restriction.

Context: End of a letter:

김철수 드림.

Yours sincerely, 김철수.

On public signs ㅁ carries a strong nuance of prohibition and demanding compliance; not just posting a factual statement. This nuance is difficult to convey in the English translations.

Compare:

진입금지

No entry

진입하지 못 함

Do not enter stronger

Compare:

일방통행

One way

일방통행임

One way only stronger

About 기

Nominaliser 기 is more productive than ㅁ and less productive 것. 기 tends to be used with unfinished activities, processes and states.

듣다 → 듣기 = 듣+기

to listen → listening

공부하다 → 공부하기 = 공부하+기

to study → studying

운전하다 → 운전하기 = 운전하+기

to drive → driving

Since 기 has been a significant nominaliser from Early Modern Korean onwards, there are a large number of grammatical constructions based on 기.

-기 전

너무 늦기 전에

before it’s too late

-기 시각하다

운전을 배우기 시작했다

started learning to drive

기 as a sentence-ender is somewhat infrequent in spoken language and restricted to non-assertive contexts. Here it suggestively solicits co-operation and has an indirect force.

놀기 없기

ridiculing isn’t okay

쓰레기 안 버리기

littering isn’t okay

Compare the above examples with (sentence-ender) ㅁ which is direct and demands compliance. 기 is used in contexts where the speaker does not want to be too harsh, such as when talking to children.

In written contexts, 기 as a sentence-ender carries a neutral force and is mostly used for actions and processes.

두번치기

Double kick (Pikachu’s attack)

빠르게 주문하기

Fast ordering

카카오톡 PC버전 설치하기

Installing KakaoTalk on PC

About M 것

Nominaliser 것 is more productive than both ㅁ and 기. It is the most versatile nominaliser and can be used almost anywhere. It can replace ㅁ and 기 in spoken language and usually doesn’t cause any change in meaning. One difference is that 것 is best used when speaking about a personal viewpoint (explained later).

Because 것 is still a bound noun, unlike the other primary nominalisers, it must occur with an adnominal modifier (ㄴ|는|ㄹ|던).

그가 먹은 것

what he ate

그가 먹는 것

what he’s eating

그가 먹을 것

what he’ll eat

그가 먹던 것

what I recall he ate

Since 것 means ‘thing’ or ‘fact’, it is sometimes used to describe ‘things’.

필요한 것

something needed

재미있는 것

something interesting

다른 것

something else

오래된 것

something old

새로운 것

something new

빌린 것

something borrowed

파란 것

something blue

Contrary to this, for the most part, the meaning of ‘thing’ or ‘fact’ actually gets lost when the phrase becomes part of a clause/sentence.

비가 온 것

(the fact that) it rained

비가 온 것을 봤다

I saw that it rained.

비가 오는 것

(the fact that) it’s raining

비가 오는 것을 봤다

I saw that it’s raining.

예쁜 것

a pretty thing

얼굴만 예쁜 것이 아니라

not just a pretty face

예쁠 것

a pretty thing

너무 예쁠 것 같아

will look really pretty

As the most productive nominaliser, 것 has virtually no preferences or limitations, except that it isn’t used when describing an objective fact.

비오는 것이 쉽다. (X)

비오기가 쉽다. (O)

It’s likely to rain. Objective

비가 올 거야. (O)

(I think) it will rain. Subjective

ㅁ vs 기 vs 것

Unlike most other aspects of grammar where there is a single form performing a single function, multiple nominalisers are performing the same faction with only slight differences. The history of nominalisers helps illustrate the competing roles of ㅁ, 기 and 것. Since these three forms perform the same function, there is considerable overlap between them. There is sometimes no discernible difference between the nominalisers because they perform ultimately the same function. However, there are some differences.

ㅁ is the least productive nominaliser in Modern Korean and has certain nuances. ㅁ tends to have the following characteristics:

• tends to be used with completed actions,

• tends to nominalise abstract thoughts and ideas,

• tends to denote entities of knowledge and belief (from a universal perspective),

• used in many fossilised nouns,

• used more often than 기 and 것 in bullet points and has the nuance of demanding compliance,

The remaining nominalisers 기 and 것 have long competed for dominance, with 것 only recently becoming more productive. Interestingly, it has been suggested that the rise of 것 is due to calquing by translators of English phrases such as the thing that is… and it is that… spreading throughout the language. This ability to easily reference an entity as “A thing that X” is what makes 것 a more powerful nominaliser than 기. The fact that 기 and 것 have long competed for essentially the same function is the reason why there is often no discernible difference between them.

기 is still a productive nominaliser and has the following characteristics:

• tends to be used with activities, processes and states,

• tends to be used with (unfinished) actions and states where time isn’t a consideration,

• used in a large number of grammatical constructions,

• used infrequently in (spoken) sentence endings, where it solicits co-operation with an indirect force,

• used commonly in bullet points, where it’s mostly used for actions and processes,

ㅁ vs 기 can be summarised by the following table, where ㅁ presents an entity and 기 presents a process.

| 살다 live | 죽다 die | 웃다 laugh |

| 삶 life | 죽음 death | 웃음 laughter |

| 살기 living | 죽기 dying | 웃기 laughing |

As the dominant nominaliser, 것 doesn’t have particular usage, unlike ㅁ and 기 which have been downgraded to certain characteristics. There isn’t much to say other than:

• tends to be avoided when 기 and ㅁ are more appropriate (which are fuzzy boundaries),

• used freely with almost any verb,

• used with the most flexibility,

• used rarely in bullet point endings.

There is one important difference between 기 and 것. 것 is exclusively used when the speaker describes what they experience (see/hear) or are aware of.

버스를 타는 게 낫겠다. (O)

버스를 타기가 낫겠다. (X)

I think it’ll be better to take the bus.

그 놈이 내가 말하는 것을 엿듣고 있다. (O)

그 놈이 내가 말하기를 엿듣고 있다. (X)

He is eavesdropping on whatever I say.

그 놈이 한국말로 말하는 걸 보고 놀랬다. (O)

그 놈이 한국말로 말하기를 보고 놀랬다. (X)

I was surprised to see the guy speaking in Korean.

너무 외로웠던 것이 생각나다. (O)

너무 외로웠기가 생각나다. (X)

I remember feeling so alone.

Moreover, compare:

한국어를 공부하기(가) 어렵다.

Studying Korean is difficult.

Stated as universal fact or personal experience.

한국어를 공부하는 것이 어렵다.

(I find that) studying Korean is difficult.

Stated as personal experience.

한국어 공부하기(가) 좋다.

Korean is good to study.

Stated as universal fact or personal experience.

한국어 공부하는 것이 좋다.

I like studying Korean.

Stated as personal experience.

여기서 공부하기(가) 좋다.

Here is good for studying.

Stated as universal fact or personal experience.

여기서 공부하는 것이 좋다.

I like studying here.

Stated as personal experience.

With the above examples, we see that 것 is used when the speaker is talking about their viewpoint (speaking for themselves); and that 기 is often used when the speaker is making a universal statement (acting as if they are speaking on behalf of everyone else).

Additional details

[Please ignore: placeholder for future update]

Associated grammar

[Please ignore: placeholder for future update]

See also

[Please ignore: placeholder for future update]

Bibliography

— Choo, M., & Kwak, H. (2008). Using Korean: A Guide to Contemporary Usage. New York: Cambridge University Press.

— Lee, I., & Ramsey, S.R. (2000). The Korean Language. Albany: State University of New York Press.

— Lee, K. (1993). A Korean Grammar on Semantic-Pragmatic Principles. Seoul: Hanʼguk Munhwasa.

— Song, J. (2005). The Korean Language: Structure, use and context. New York: Routledge.

— Rhee, S. (2008). On the rise and fall of Korean nominalizers. In M. J. López-Couso & E. Seoane (Eds.), Rethinking Grammaticalization: New perspectives (pp. 239–264).

— Rhee, S. (2011). Nominalization and stance marking in Korean. In F. H. Yap, K. Grunow-Hårsta & J. Wrona (Eds.), Nominalization in Asian Languages (pp. 393–422).

— Yeon, J., & Brown, L. (2008). Korean: A Comprehensive Grammar. New York: Routledge.