Contents

Introduction

Bound nouns

Plurals

Nominalisation

Pronouns

Additional details

Associated grammar

See also

Bibliography

Introduction

The word ‘noun’ comes from thr Latin ‘nomen’ meaning ‘name’. Nouns are the names given to things in the world. A book is something made of papers bound together and is used for learning/enjoyment. The word ‘book’ is the name given to this item.

The Korean nameword for ‘noun’ is 명사(名詞) where 명(名) means ‘name’. This character comes from 夕 (shape of the crescent moon) and 口 (shape of the mouth). The only way to identify ourselves in the dark is to say our names. This is how nouns work; they give light to things in the world.

Korean nouns come after modifiers and before particles.

검은 고양이가

black cat

Bound nouns

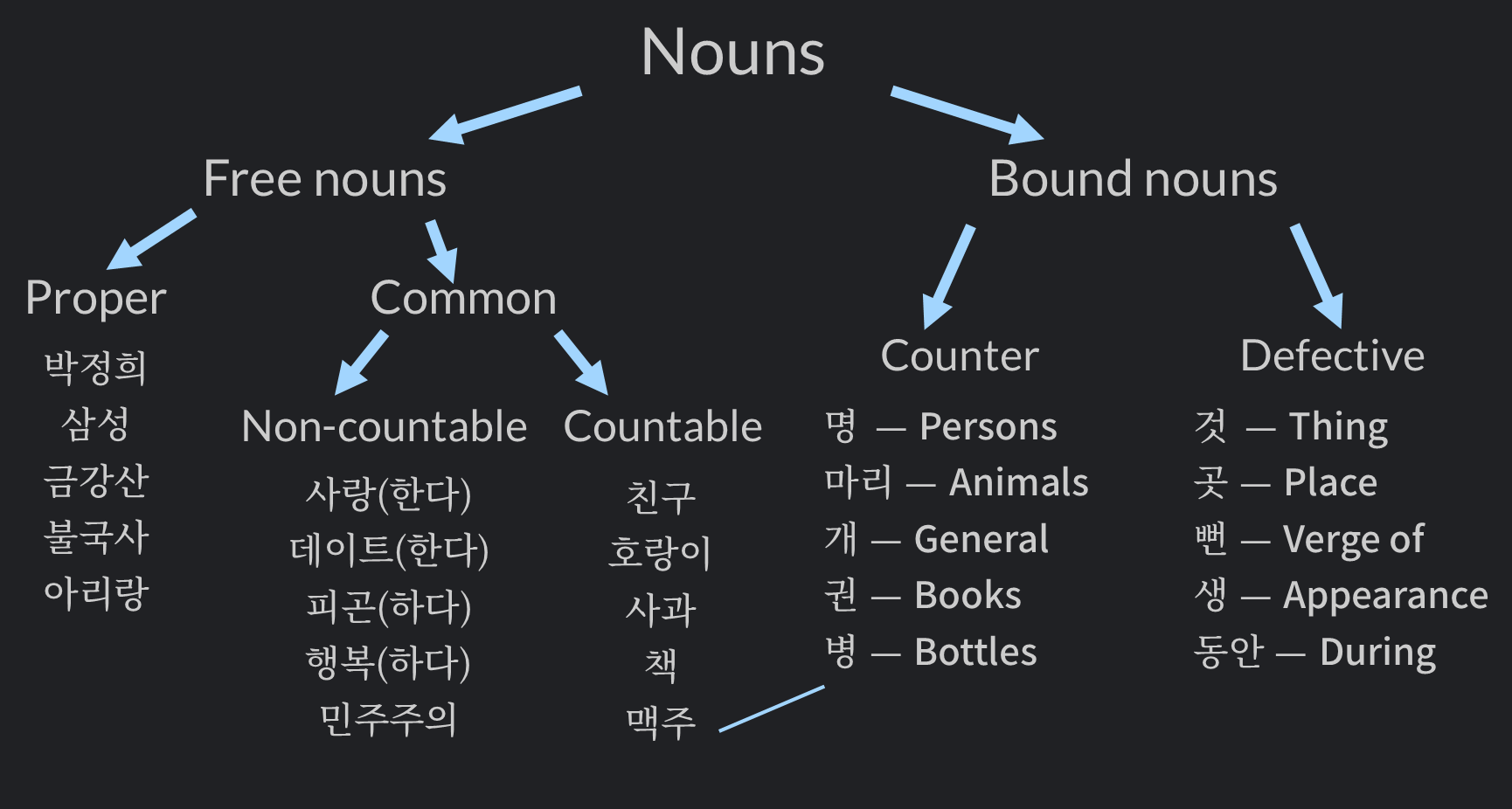

In Korean, there are two types of bound nouns (nouns which do not appear independently), counter nouns and defective nouns. Counter nouns are required when counting items.

[item] [number] [counter]

고양이 세 마리

Three cats.

Defective nouns on the other hand are used in modifying expressions:

이 것

this thing

예쁜 것

a beautiful thing

언니것

Sister’s thing

See the respective entries for more details.

Plurals

Korean nouns do not have singular and plural forms.

Compare:

고양이 한 마리

one cat

고양이 세 마리

three cats

In certain contexts, -들 can be used to mark plurality. When exactly to mark nouns with -들 is a common question among Korean learners. -들 most frequently occurs with human nouns and less frequently with (non-human) animate nouns. It’s rarely used with inanimate nouns. Even with human nouns, -들 is usually omitted because plurality is often indicated in its absence. For example, 사람 and 사람들 can both indicate multiple people (by contextual clues).

친구 많이 있다.

I have lots of friends.

Here the use of -들 would be unnatural because plurality is indicated by 많이. In the same way, -들 is never used with counters where plurality is already indicated (친구 세 명).

One instance where -들 is always used is with demonstrative words (이, 그, 저). This is because speakers need to distinguish between referring to one person or multiple people (그 사람 VS 그 사람들).

Nominalisation

Nominalisation is where something (usually a verb) becomes a noun.

먹다 → 먹이 = 먹+이

to eat → food

지우다 → 지우개 = 지우+개

to erase → eraser

막다 → 마개 = 막+애

to clog → a plug

지다 → 지게 = 지+게

to carry (on the back) → wooden frame for carrying loads on the back

묻다 → 무덤 = 무+엄

to bury → grave

맞다 → 마중 = 맞+웅

to meet/face → a meeting

걷다 → 걸음 = 걸+음

to walk → a step

여행하다 → 여행하기 = 여행하+기

to travel → (act of) travelling

공부하다 → 공부하는 것 = 공부하+는 것

to study → (act of) studying

Here the verb takes a nominaliser (이, 개, 애, 게, 엄, 웅, (으)ㅁ, 기, M 것) and becomes a noun. The productive nominalisers (the ones to know) are ㅁ, 기 and 것. 이 is sometimes used, though is usually found in fossilised nouns. The remainder mentioned above are only found in a few fossilised nouns and are presented only for illustrative purposes.

-지 is sometimes also considered a nominaliser, though its status as such depends on different perspectives of grammar. Historically, it originated from 기.

Certain grammar patterns are built on nominalisation. For instance:

-기 시작하다 (to start)

비가 오기 시작했다

It began to rain

See the entry on nominalisation for more details.

Pronouns

[Please ignore: placeholder for future update]

Additional details

[Please ignore: placeholder for future update]

Associated grammar

[Please ignore: placeholder for future update]

See also

[Please ignore: placeholder for future update]

Bibliography

— Chang, S.J. (1996). Korean. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

— Lee, I., & Ramsey, S.R. (2000). The Korean Language. Albany: State University of New York Press.

— Martin, S. E. (1992). A Reference Grammar of Korean. Singapore: Tuttle Publishing.

— Sohn, H. (1999). The Korean Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

— Song, J. (2005). The Korean Language: Structure, use and context. New York: Routledge.